Leading Effective Discussions with Socratic Questioning

Students often lose points for their discussions because they

- don’t have a clear aim or direction

- suggest and/or impose the leader’s view

- aren’t fully inclusive – discussants are allowed to contribute little

- don’t encourage critical thinking – discussants are allowed to simply state their opinions/feelings

You can benefit from ancient Greek philosopher Socrates’ method of dialogue to give structure and meaning to the group discussions you will lead.

Socrates once famously described himself as a “horse-fly”, forever trying to sting the Athenian people into a fully conscious examination of their beliefs, assumptions, and actions. His method for doing this was to question them mercilessly until they lost sight of their comfortable certainties, and glimpsed the “aporia,” or confusion, where the possibility of change resides.

This lesson looks in detail at the four directions and six question types of the Socratic method. Scroll to the bottom of this page for a summary task about your own discussion questions.

Socratic Discussion – The Four Directions of Thought

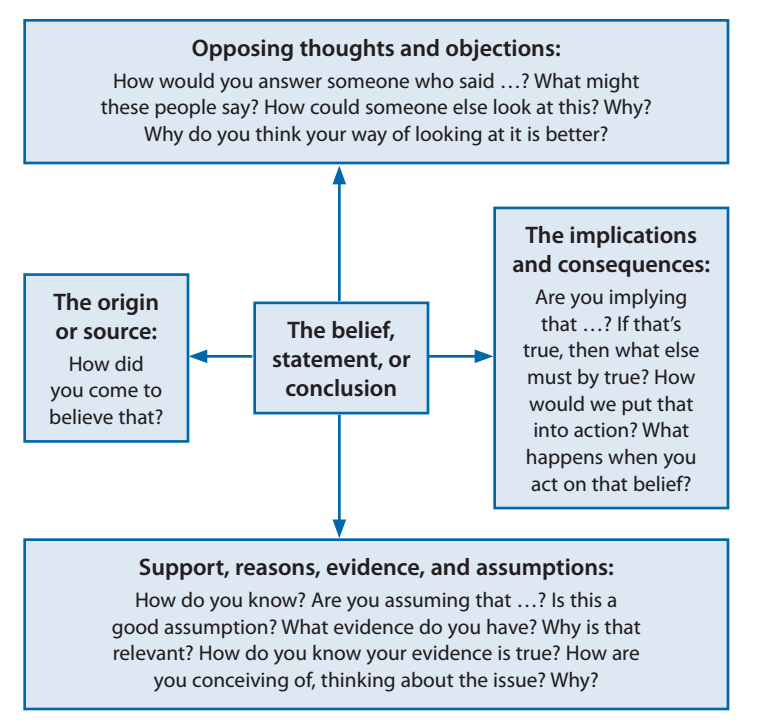

Critical thinkers like to talk about the “four directions” human thought can take. Every person’s thinking is the product of a history of prior belief, conscious reasons and evidence, opposing others’ viewpoints, and considering the implications and consequences of their ideas. Study the diagram below to to see the aspects of a discussant’s ideas that you can question with the Socratic method.

Six Types of Socratic Question – Adapted from Paul & Binker (n.d.)

Richard Paul has divided the questions in Socrates’ dialogues into the following six types:

QUESTIONS OF CLARIFICATION

- What do you mean by …?

- What is your main point?

- How does relate to … ?

- Could you put that another way?

- Is your basic point that …. or that …?

- What do you think is the main issue here?

- Let me see if I understand you; do you mean that … or that …?

- How does this relate to our discussion (problem, issue)?

QUESTIONS THAT PROBE ASSUMPTIONS

- What are you assuming?

- What is Karen assuming?

- What could we assume instead?

- You seem to be assuming . Do I understand you correctly?

- All of your reasoning depends on the idea that . Why have you based

- your reasoning on rather than ?

- You seem to be assuming . How would you justify taking this for

- granted?

- Is it always the case? Why do you think the assumption holds here?

- Why would someone make this assumption?

QUESTIONS THAT PROBE REASONS AND EVIDENCE

- Whv do vou sav that? How do you know?

- Why do you think that is true? What led you to that belief?

- What would be an example? Are these reasons adequate?

- Do you have any evidence for that? How does that apply to this case?

- What difference does that make? What would change our mind?

- What are your reasons for saying that?

- Could you explain your reasons to us?

- Could you give me an example? Would this be an example: ?

- Could you explain that further? Would you say more about that?

- But is that good evidence to believe that?

- Is there reason to doubt that evidence?

- Who is in a position to know if that is so?

- What would you say to someone who said that … ?

- Can someone else give evidence to support that response?

- By what reasoning did you come to that conclusion?

- How could we find out whether that is true? What other information do we need?

QUESTIONS ABOUT VIEWPOINTS OR PERSPECTIVES

- You seem to be approaching this issue from perspective. Why have you chosen this rather than that perspective?

- How would other groups/types of people respond? Why? What would influence them?

- How could you answer the objection that would make?

- What might someone who believed think?

- Can/did anyone see this another way?

- What would someone who disagrees say?

- What is an alternative?

- How are Ken’s and Roxanne’s ideas alike? Different?

QUESTIONS THAT PROBE IMPLICATIONS AND CONSEQUENCES

- What are you implying by that?

- When you say that …, are you implying ?

- But if that happened, what else would happen as a result? Why?

- What effect would that have?

- Would that necessarily happen or only probably happen?

- What is an alternative?

- If this and this are the case, then what else must also be true?

- If we say that this is unethical, how about that?

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE QUESTION

- How can we find out? Is this the same issue as ?

- What does this question assume? How would put the issue?

- Would put the question differently? Why is this question important?

- How could someone settle this question?

- Can we break this question down at all?

- Is the question clear? Do we understand it?

- Is this question easy or hard to answer? Why?

- Does this question ask us to evaluate something?

- Do we all agree that this is the question?

- To answer this question, what questions would we have to answer first?

- I’m not sure I understand how you are interpreting the main question at issue.

TASK: Review your Discussion Questions

Look at the discussion questions you have prepared. Ask yourself:

- What is the aim or purpose for your discussion? What exactly would you like discussants to discover or explore? When can it be considered complete? Tell them at the start.

- Do you have discussion questions which explore the four directions of thought? i.e.,

- support, reasons, and evidence

- origins, beliefs, assumptions

- opposing and/or alternative views

- implications and/or consequences

- Note down some follow-up questions that ask discussants to think about

- clarifying/explaining their view

- their prior assumptions/beliefs

- giving reasons/evidence

- other viewpoints/perspectives

- possible implications/consequences

- the question itself

References

Paul, Richard, Linda Elder, and Foundation for Critical Thinking. 2016. The Thinker’s Guide to the Art of Socratic Questioning: Based on Critical Thinking Concepts & Tools. Tomales, Calif.: Foundation for Critical Thinking.