What is common between DNA , all the genetic information in your cells, and plastic shopping bags? All of these “materials” are composed of long molecular chains that we refer to as polymers. Polymers, whether as constituents of biological or synthetic materials, can share common properties; they can respond to external stimuli, such as mechanical forces, electric fields, flows, or alterations in pH levels or temperature/concentration. They can also transiently adapt geometrical constraints. While type of polymeric soft matter, on one hand, provides unprecedented survival and evolutionary capabilities for life (e.g., the compaction of meters-long DNA in a protective nuclear shell), on the other hand, it creates new opportunities to design next-generation materials and pharmaceutical solutions.

Research in our lab focuses on fundamental problems related to polymers in biological and materials, such as DNA organization and hydrogels, on which we currently have little to no understanding. Specifically, we study the chromosome organization in cells and the potential role of protein-DNA interaction kinetics on this 3D organization . We are also interested in stimuli-responsive properties of polyelectrolyte hydrogels and polymer brushes. In our investigations, we use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations at both atomic and coarse-grained levels, along with analytical tools from statistical mechanics.

Research Highlights

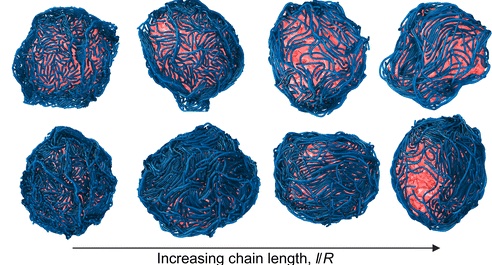

- How does the heterochromatin affect the mechanical properties of the cell nucleus?

The nucleus is more than a vault for DNA — it is also a mechanosensor that resists deformation and transmits physical cues to the genome. In a new modeling study, Attar et al. show that this mechanical resilience hinges on how heterochromatin is connected to the nuclear lamina. Using a coarse-grained polymer simulation of chromatin inside an elastic shell, the authors demonstrate that neither extra heterochromatin nor increased internal crosslinking alone stiffens the nucleus. Only when heterochromatin is tethered to the lamina does the nucleus gain robust, strain-dependent stiffness, with crosslinking providing a secondary boost. Our recent work by our former MA student A. Goktug Attar in colloboration with our collugues from University of Silisia (Poland) and MIT (US) recasts heterochromatin as a mechanically active scaffold whose anchoring to the nuclear periphery underpins nuclear integrity and mechanotransduction — a finding that could reshape how we think about nuclear organization in development, disease and cell migration. Read more on Nucleic Acid Research.

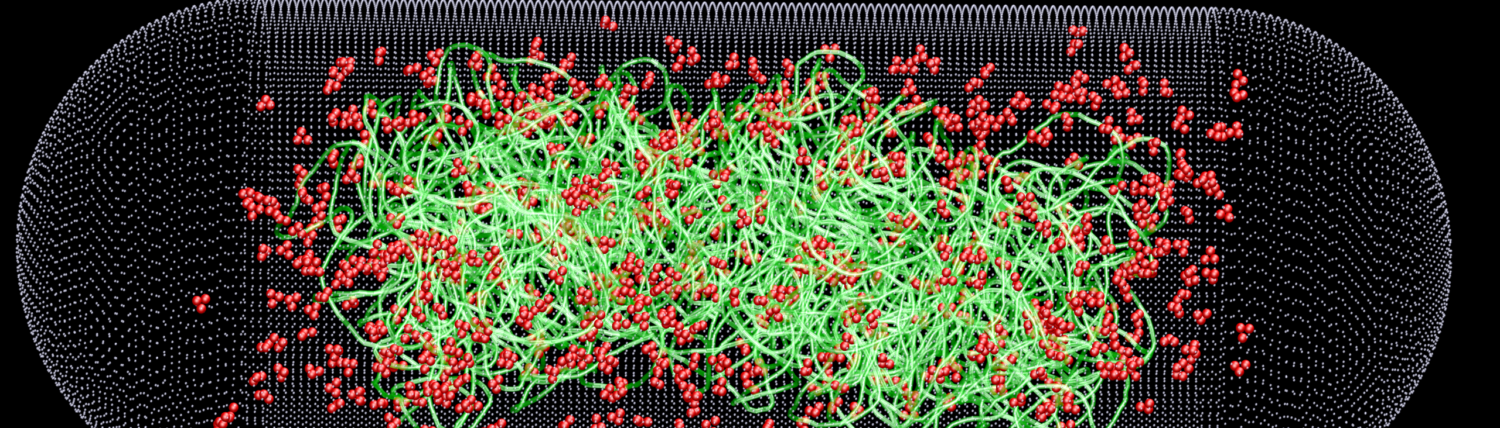

- Controlling the Shape of Soft Biological Shells with Surface-Bound Polymers

Biological shells such as cell nuclei, membranes, and vesicles often deviate from spherical shapes due to interactions with molecular components at their surfaces. In this work, we investigate how many semiflexible polymers adsorbed onto a soft, pressurized shell can collectively reshape it. Using coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations, we model a spherical elastic shell and systematically vary polymer–surface attraction strength, polymer concentration, and chain length.We find that strong surface localization of polymers induces significant shape distortions and reduces shell size. In contrast, weak localization leaves the shell nearly spherical but promotes nematic ordering of polymers on the surface. When the polymers are comparable to or longer than the shell radius and the shell behaves in a liquid-like manner, this surface ordering can drive the shell into elliptical shapes. Our results show how collective surface organization of semiflexible polymers provides a physical mechanism to control soft-shell morphology, with implications for both synthetic materials and biological systems. Read more on Soft Matter!

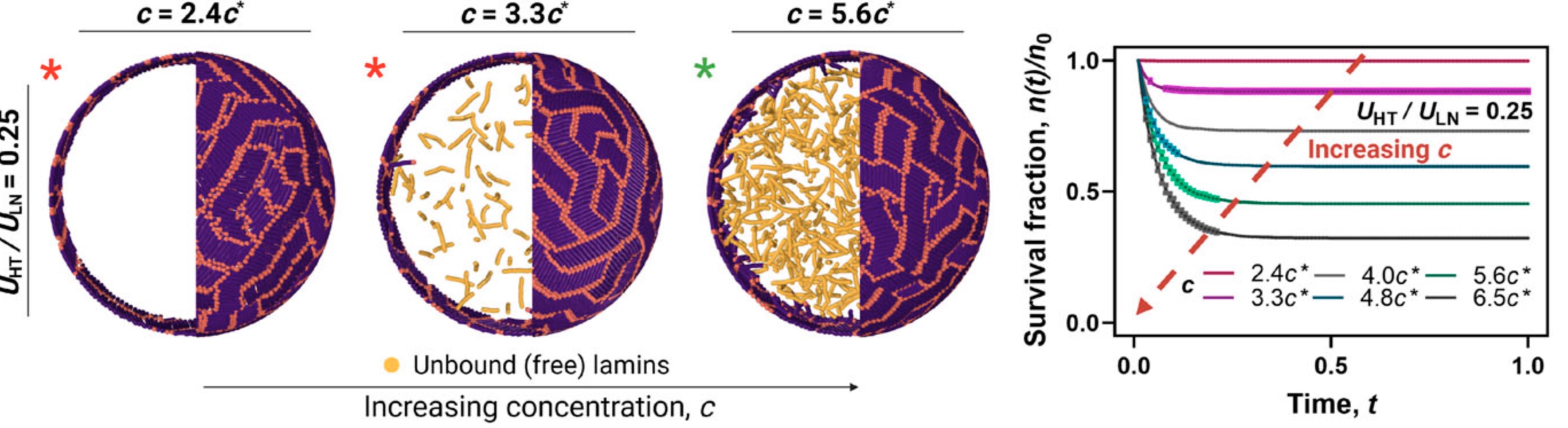

- Physical Mechanisms of Nuclear Lamina Remodeling in Laminopathies

The nuclear lamina, a two-dimensional meshwork of lamin proteins at the nuclear periphery, provides structural integrity and shape to the cell nucleus. In laminopathic diseases such as Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome, lamin filaments assemble into an abnormally thick lamina and form highly stable, liquid-crystal–like nematic domains, profoundly altering nuclear mechanics and morphology. In this work, we model lamin filaments as coarse-grained rod-like polymers confined within a spherical shell to investigate their aggregation and dissociation dynamics. Our simulations reproduce the emergence of multidirectional nematic domains and the reduced lamin turnover observed in diseased nuclei. We show that lamina thickness is primarily controlled by head–tail (lamin–lamin) interactions, while nematic ordering requires sufficiently strong lamin–shell affinity. Additionally, lamin unbinding exhibits concentration-dependent facilitated dissociation that is suppressed by strong intra-lamin interactions, providing a physical explanation for the abnormal stability of the lamina in laminopathic conditions. Read more on JCP!